One of the hottest new books of 2023 was The Guest by Emma Cline. The novel follows a 22-year-old call girl from New York City named Alex, as she wanders through the Hamptons, going from party to party, harboring an unreasonable hope that she can get back together with her wealthy boyfriend, Simon, in the week leading up to Labor Day. The Guest is simultaneously funny, tense, surreal, and an overall great read.

But throughout the book, I had a weird sense of déjà vu. Why did it feel like I had read this before? The Guest is oddly reminiscent of John Cheever’s classic short story “The Swimmer.” Like Cline's novel, Cheever’s 1964 short story follows a fallen person as he makes a foolhardy effort to swim “across the county” via pools of his “friends” to get home. Both The Guest and “The Swimmer” feature striking similarities: Both involve a foolish journey, both are surreal, both are poignant social commentaries on the rich and—possibly most importantly—both highlight a sense of precarity in contemporary life.

These parallels are not a hallucination. In an interview with Interview Magazine, Cline said “It’s very loosely inspired by ‘The Swimmer.’” The assertion that The Guest is “very loosely inspired” by Cheever’s work seems dubious to me and that’s okay. I personally love the idea of repurposing older material and updating it for current times. And I especially love the idea of repurposing and reinvigorating John Cheever’s body of work.

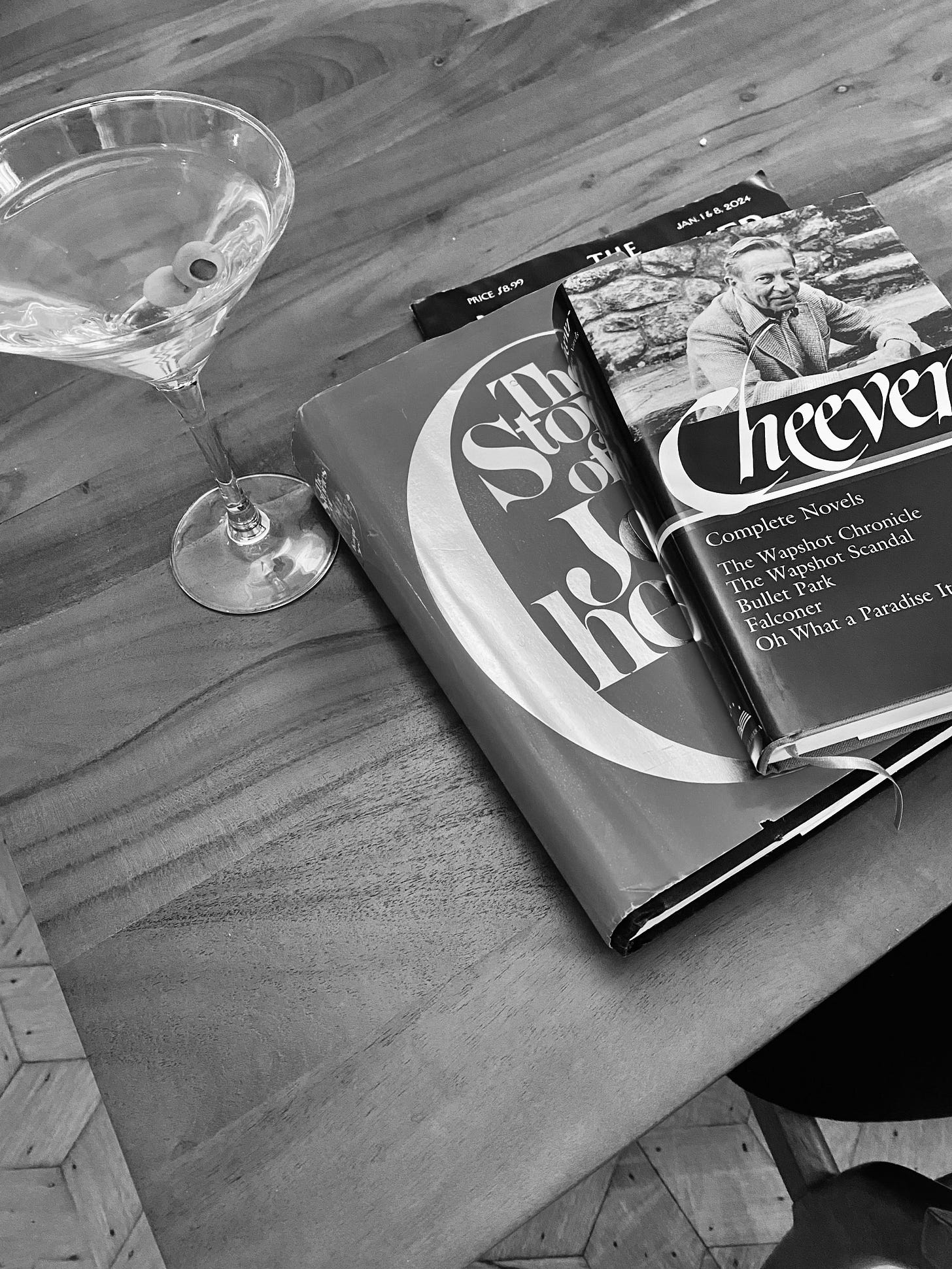

Unfortunately, as Cheever’s biographer Blake Bailey wrote, not much of Cheever’s work is “is read much anymore” and he “is hardly taught at all in the classroom, where reputations are perpetuated.” I would ascribe this to two key reasons. The first is that John Cheever’s novels are good, but not great. There is nothing particularly transcendent in them. This is in sharp contrast to his short fiction, which I would argue is certainly transcendent (more on that later). His novels—particularly his most notable works, The Wapshot Chronicle and Falconer—while good reads and well-reviewed at the time of publication, are a bit plodding. He may be able to write “the tightest paragraph in American fiction,” but that does not mask the fact that Cheever’s novels can be a bit of a bore.

My second conjecture for why Cheever’s work is overlooked today is his association with a group of writers David Foster Wallace called “the Great Male Narcissists who’ve dominated postwar realist fiction.” John Cheever is lumped together with writers like Norman Mailer, Philip Roth, Saul Bellow, and most notably John Updike. Today the militant machismo and sexism of these men’s writing and personalities is not as attractive as they once were and seem to have dragged down the status of these men (with a slight exception for Roth, who has undergone a bit of a renaissance of late).

Yet, I think conflating these writers with Cheever is misguided. Yes, Updike and Cheever wrote about nearly identical subjects (American suburbia and the emergent yuppie class) and were contemporaries. They knew each other and were frenemies, so to speak. While both concerned themselves with taking on Norman Rockwell’s vision of America, Cheever and Updike came to the subject from very different angles. Updike does little to tweak the Rockwellian vision of America, aside from giving it a sybaritic edge. If one reads Updike’s work—notably the Rabbit Angstrom series of novels, Couples, The Witches of Eastwick, and his series of short fiction on the dissolution of Joan and Richard Maple’s marriage—one does not come away with the feeling that the classic Norman Rockwell aesthetic thesis is wrong. Sure, there is more sex, but in the end, everyone is fine and goes on living their privileged lives.

But what differentiates Cheever is the fact that his writing, particularly his short stories, rejects the Rockwell-Updike idea of midcentury America. While Updike’s body of work can largely be described as an exaltation of privilege, Cheever’s writing is more of an exploration of precarity. More specifically, Cheever’s work focuses in on how one’s privileged position in life is precarious, and one martini, one bad decision could destroy everything.

It is this sense of precarity and impending doom that makes Cheever a worthy read in 2024. In this new age of anxiety, the desire to shed our old hedonistic ways in favor of a new healthy lifestyle seems to be reaching a fever pitch. I cannot say what is driving this, there is certainly something in the air that is compelling Americans to live a healthier lifestyle.

This is evident in how Americans are drinking less booze. According to a recent Gallup Poll, the number of young Americans is declining precipitously. And Cheever, despite his personal rampant alcoholism, wrote poignantly about the dangers of alcohol. Take “The Sorrows of Gin” or “The Swimmer,” both are short stories about how boozing and partying can destroy a family.

And Cheever’s other work dives deep into other anxieties that are plaguing American life. In “Christmas Is a Sad Time for the Poor,” Charlie, a working-class elevator operator in a ritzy Manhattan apartment building, is the beneficiary of the residents’ nobless oblige until they spurn him for being too amiable. This story plays nicely into our contemporary discourse surrounding the one percent crowd, as well as the precarity of employment in today’s economy. Another story of Cheever’s, “The Enormous Radio,” is incredibly prescient and explores the anxiety of new technology eerily reminiscent of social media. Even the novel The Wapshot Chronicle, which is all about the Wapshot family’s financial decline and uncertainty due to changing economic circumstances, speaks to themes that are rampant in our current discourse.

There is something timely about the existential doom that looms over Cheever’s opus. He touches on many of the underlying feelings that make our contemporary times feel so tenuous. Whether it is anxiety over drinking, financial insecurity, class disparity, and the ills of social media, that can all be found in Cheever’s writing. Even John Cheever’s personal life feels oddly contemporary. He was a struggling writer for most of his life, he had trouble affording a place to live, he embraced his homosexuality, and he spoke openly about his struggles with alcoholism.

Despite being dead for more than 40 years, John Cheever, the Chekov of the Suburbs, “the Boccaccio of midcentury America,” is decidely a talent befitting of 21st-century readers. Yet, Cheever is falling into obscurity, undeservedly tossed into the literary ash heap. But, his work deserves to be resurrected. Cheever needs to be read.